Can you catch a culprit with a can and some string?

It’s a fall afternoon in Apollo in 1921. As as a trim blue-eyed man named Clark Owens Truby sifts through his mail, he comes across an unusual letter. Clark, age 31, is a grandson of Apollo farmer Simon Truby, and he’s living in the old Truby farmhouse with his wife Nellie, his 5-year-old son Jack, and his widowed father Henry Hill Truby, age 71. The letter is addressed to Clark, and it demands that he place $100 at the far corner of his dad’s backyard chicken coop. If he fails to do so, the letter states, Clark Truby will be killed. The letter is signed “Black Hand.”

Apparently, Clark took his chances and took no action. So six days later, on October 25, Clark found a similar note pinned to the Truby kitchen door, this time demanding $200 and telling Clark to “do as we told you, or we will shoot you on sight.” The next day, a third message tacked to the backyard chicken coop warned: “This is your last chance.” If the money was not in place that night, Clark’s entire family would be murdered.

That’s when Clark Truby turned the three notes over to Vandergrift burgess W A McGeary, who contacted Pennsylvania State Police headquarters in Greensburg for assistance. Private John J Tometchko was assigned to the case.

“Do as we told you, or we will shoot you on sight.”

—Black Hand

Turns out, Clark Truby wasn’t the only one in the Pittsburgh and Kiski area who’d been receiving threatening letters signed “Black Hand.” Such letters purportedly came from the mafia-linked Black Hand Society, which had origins in Italy. But sometimes they came from local copycats who wanted some quick cash. Black Hand letters often threatened death or destruction of property if payment demands weren’t met. The Pittsburgh papers were filled with stories of murder or mayhem when recipients of Black Hand letters failed to pay up.

By the early 1920s, Vandergrift, Leechburg, and Apollo residents were also receiving Black Hand letters. In fact, about a month before Clark Truby received his notes, several Black Hand letters had been sent to Apollo resident James Maccagne, who owned a store and home near the railroad tracks. Around September 14, 1921, Maccagne noticed an explosive-looking device on his property. He picked it up(!) and threw it toward the railroad tracks, where it exploded, breaking several nearby windows and damaging the street. A year earlier in Leechburg’s business district, police suspected a Black Hander was behind a water main explosion and the burning of two commercial buildings owned by J C Wolf and Joseph Angross, which caused about $50,000 in damages (about $700,000 today).

Needless to say, local nerves were jangly and raw. According to an October 1921 article in the Vandergrift News Citizen newspaper:

Apollo has been polluted with blackhand letters for the past two months, and it is claimed that prominent men who have received notes demanding money keep all the lights in their homes burning at night and an automatic handy. It is said that a man who had been a very heavy drinker has been sober ever since he received a blackhand letter.

Perhaps the ladies of Apollo’s WCTU (Women’s Christian Temperance Union) felt gratified to know that Black Hand letters might help turn gentlemen away from the evils of drunkenness.

The current rash of Black Hand letters involving Clark Truby and others seemed different from the earlier threats and local explosions. This new “Black Hand” apparently sent six letters through the US mail in late October to four men: Clark Truby; Charles Truby (Clark’s uncle); Alex Culp; and William Benner, all of Apollo. The latter three were each told to place $300 in a tin can and conceal the can and money at a specific tree in Apollo. Culp was told if he did not do so “we will kill your family.”

“It is said that a man who had been a very heavy drinker has been sober ever since he received a blackhand letter.”

Vandergrift News Citizen

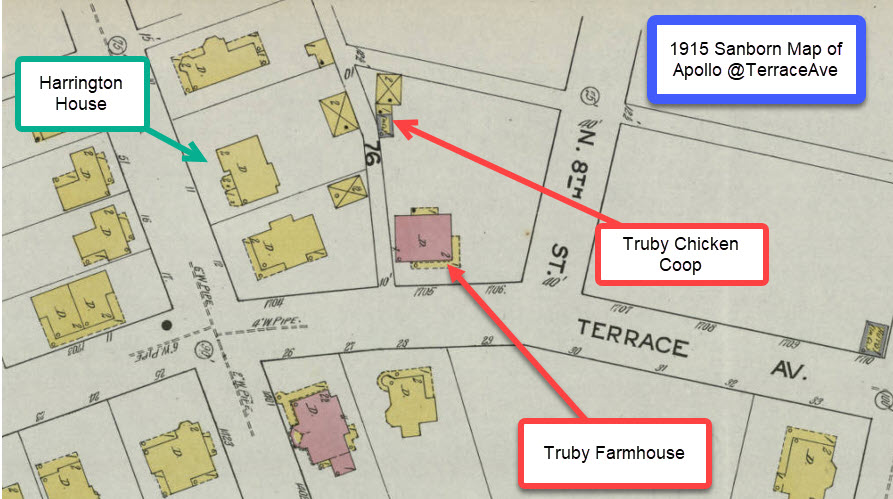

State policeman Tometchko met up with Clark Truby at the Truby farmhouse, 708 Terrace Ave, on the “last chance” day of reckoning—Wednesday October 26, 1921. The two men went out back to inspect the chicken coop, and they hatched a plan. All they needed was a tin can, scraps of paper, a dollar bill, and a long piece of string (MacGruber, anyone?).

First, Truby created a decoy payment by wrapping the dollar around a roll of scrap paper, placing the bundle in the can, and attaching a long string to the can. Tometchko would hide in the hen house beginning late afternoon. Toward evening, Clark would bring the decoy can to the designated location, and he’d toss the other end of the string to the officer concealed in the coop. When the perpetrator grabbed the can, the string would pull taut and Tometchko could capture the Black Hand red-handed.

Under the afternoon sun, Tometchko looked around to ensure no one was watching. Then he clambered into chicken coop and crouched down near the door. According to the Pittsburgh Press, “The chickens clucked, ruffled their feathers, and made a great hub-bub. They crowded over to the far side of the chicken house and eyed the intruder speculatively, turning their heads from side to side. … The trooper shifted the muscles of his cramped body carefully, so as not to alarm the chickens. …”

Around 7:30 pm, as planned, Clark placed the tin-can decoy in the alley next to the hen house, and he tossed the long end of the string into the coop, within Tometchko’s grasp. The officer shifted the string from one hand to the other as he waited.

About 4 hours later, around 11:15 pm, Tometchko heard someone walking close to the chickenyard fence. He felt the tug of the string as someone in the alley picked up the can and began to run. Tometchko yelled “Halt” as he ran in pursuit, but he didn’t have far to go. The officer nabbed the fugitive as he was about to enter his home, which happened to be just across the alley from the chicken coop. The can was in his pocket.

The suspect was essentially a backyard neighbor of Truby’s—a lanky 25-year-old blue-eyed brown-haired man who lived with his parents and siblings in a large house at 520 N. 7th Street, a property that backed onto the same alley as the Truby chicken coop. The man now in custody was named George Leslie Harrington, and he was from a “prominent Apollo family,” according to the Vandergrift News Citizen.

Cute little George Leslie Harrington of Apollo, at about age 7…long before he called himself the Black Hand.

Also, dear readers, I was stunned to learn that the perpetrator happened to be my great-great uncle—Uncle Les. This piece of family history was completely unknown to all of my living relatives. So this might be a cautionary tale, if you’ve ever considered doing family research: Be prepared to uncover surprising skeletons in the family closet. For folks who’ve grown up in and around Apollo, PA, you don’t have to scratch too far below the surface to find unexpected intrigues between friends and families, going back generations.

The Apollo Black Hand story was widely covered by the press at the time. A Vandergrift News Citizen reporter was the first on the scene, apparently interviewing Harrington the night of his arrest, because a front-page story appeared the next morning, on October 27, 1921. The News Citizen described the trap that was set in Apollo at the home of Mike Truby (Clark Truby also went by the first name Mike), and it describes the daring capture by the state police. About the perpetrator, the story notes:

Harrington is a mild and pleasant mannered young fellow and entirely different from what one would expect a blackhander to be. He considers the matter more in the nature of a joke and not a serious matter as it really is. … he was out of work and wanted money to take him to school. While the letters threatened that the victim would be shot in case of refusal to hand over the money demanded, young Harrington said he didn’t own a revolver and had nothing to shoot with. He said that a relative of his had received a blackhand letter and that is where he got the idea.

Poor Uncle Les didn’t seem to realize he’d just gotten himself into a world of trouble. Family members who knew Les Harrington seriously doubt he wanted the money to further his education, as he told the reporter. But the Harrington family had fallen on hard times shortly before Les’s arrest, which might explain (but doesn’t excuse) his desperate attempts to extract money from neighbors.

Les’s dad, Alfred Harrington (my great-great grandfather), was co-owner of an oil & gas drilling firm at the turn of the century and had become quite prosperous. A profile of Alfred Harrington is featured in the History of Armstrong County Pa, Volume 2, by J H Beers. That book was published in 1914. The following year, Alfred Harrington died suddenly from a stroke, likely brought on by a head injury sustained while he surveyed a gas or oil field during a storm. Alfred’s widow, Cora Leslie Harrington, was squeezed out of receiving any proceeds from the business her husband had founded, and the family—with three children still at home—fell on hard times. To make ends meet, Cora gave piano lessons and eventually divided her large house on N. 7th Street into three rental apartments—one on each floor. Cora Harrington also played piano and sang in the quartet of Apollo’s Presbyterian Church on First Street.

The morning of his arrest, George Leslie Harrington appeared before Vandergrift Justice of the Peace J A Bair and pleaded guilty to charges of attempted blackmail. He was taken to Greensburg on the noon train, and was photographed and fingerprinted at state police headquarters. On Monday October 31, Harrington was turned to the custody of the US postal inspector, because his crime involved federal mail, and he was committed to the Allegheny County Jail to await further action.

On Friday November 18, 1921, Harrington was found guilty of violating postal laws (i.e., using mails to defraud), and he was sentenced to serve a year and a day in federal prison in Atlanta. While there, Harrington wrote often to his family and to his sweetheart Sadie Walter, whom he married mid-way through his sentenced term—in March or April 1922. Les Harrington was released a few months early, on September 8, 1922, for good behavior.

But what of Clark Owens Truby, the original victim of this tale? I’m sad to report that it seems the Black Hand caper was just one of many difficulties that Clark Truby had to face during the 1920s. Five years after the chicken coop caper, Clark’s wife Nellie Kunselman Truby died at age 30 of kidney disease, leaving Clark a single dad with a 10-year-old son. The following year, in 1927, Clark’s father Henry Hill Truby died at age 77, leaving Clark and his son Jack living alone in the big old farmhouse. Clark’s older brother Seibert Truby, who lived next door, also died in the early 1920s. Then in December 1928, Clark lost ownership of the Truby farmhouse for not keeping up with mortgage or tax payments. Clark was the third and final Truby to own the Terrace Ave farmhouse.

After he lost the Apollo house, Clark continued his work as a clerk in the Vandergrift steel mill. He and Jack moved into the home of Clark’s second-cousin Harry T. Henry Jr, who was living at 120 E Madison Ave in Vandergrift with his wife, daughter, and mother- and father-in-law. Clark and Harry both worked in the mill, which was in easy walking distance.

Though the 1920s seemed rather dire for Clark Truby, might there be a happier outcome to his tale? I’ll aim to share some answers in an upcoming blog post. Myself, I’ve always been rooting for the widowed millworker Clark and his son Jack, who grew up to serve in U.S. Marine Corps in Korea during World War II.

As an addendum to this story, I’d like to give a major appreciative shout out to the Victorian Vandergrift Museum and Historical Society, which maintains an excellent archive of old newspapers, especially the Vandergrift News Citizen, on microfilm. Though the newspaper isn’t digitized and searchable online, if you know the approximate date of an important event, you can scan through the microfilms to see if the story was covered in the Vandergrift papers. The News Citizen article about the Black Hand caper was one of the most detailed that I found, and the Vandergrift reporter seems to be the only one who interviewed the Black Hand himself, Les Harrington. Too bad that reporter wasn’t given a byline!

If you love local history, please continue to support our regional nonprofit historical societies. Thanks for reading!

-by Vicki Contie

Catonsville, MD

Great article, as usual, Vicki! Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. Thanks for sharing your knowledge and talents. I grew up at 808 Terrace Ave so I’m familiar with the Truby House. Love learning the history this home holds.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love your history of the Truby family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always enjoy your posts on the Truby’s. I’ve never been able to find any relationship to these families, even though I grew up in Leechburg and rural Apollo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This story was so interesting and it enlightened me. I always loved the Truby house. One of my best friends growing up lived there, Christy Farineau Barnhart. I knew I had relatives named Truby but didn’t know I was related to this Truby family. As I read the article and saw the name Clark Truby, that didn’t ring a bell. Then I saw his wife’s name was Nellie and son’s name was Mike. I immediately called my sister, Lynda McGeary Yeany, and said this sounds like our Uncle Mike doesn’t it? Sure enough, it was. Of course I didn’t know Clark but knew they called Uncle Mike’s dad Mike also. Nellie was my grandmother’s sister. After Clark lost the house, he and Mike went to live with my grandparents, Harry and Ruth Henry and my mother Helen Henry Walker. My grandmother was like a mother to Uncle Jack after that. Uncle Jack was in the Marines and he, Aunt Mary and their two children, Mike and Patty would come and spend summer vacations with us. When I moved to Jacksonville, Florida in 1984 I stayed with Uncle Jack and Aunt Mary for a few weeks until I found an apartment. This was truly an enjoyable evening learning some of my family history and sharing it with my sister, Lynda. Of course I then called Christy and we had to chat about the history of her childhood home. Thank you! I have now subscribed to your blog and will I’m sure continue to be enlightened.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Jill, Thanks so much for writing in, and I’m glad you uncovered this additional piece of your family tree! I’m really delighted to hear from relatives of Clark & Jack Truby (I wonder why they both had the nickname Mike? – it’s curious!). I especially l0ve hearing of your happy memories of time with Jack & his wife Mary, because when I started this research, Clark & Jack’s story seemed to take such a sad turn in the 1920s, and I had trouble figuring out whatever became of Jack afterward. Clark & Jack were fortunate to have such supportive in-laws in the Kunselman and Henry families. There’s actually a circular loop involving the Henry, Kunselman & Truby families, because Harry T. Henry Jr, (married to Ruth) had a grandmother named Mary Jane Truby, the first daughter of Apollo’s Simon Truby; Mary Jane married Civil War veteran William Henry Henry, and their oldest child was Harry T Henry Sr. It’s hard to keep it all straight! Thank you again for sharing your memories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jill, your submission is amazing, and it is such a small world. I loved growing up in that house, and if my grandparents, Paul and Ellen Mae Adams, hadn’t purchased the beautiful Truby home, I would have never have had that blessing. To this day, Jill Walker Fauth remains a beloved and cherished friend. Signed, Christy Farineau Barnhart

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m so glad you’re sharing the Truby history again — I truly love the house and learning about it and the family. It brings me closer to the old neighborhood, which I miss so much. I must say that The Black Hand is such a dramatic name, and apparently he was quite the dreamer. Thanx for this wonderful story!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is there any further attributions with that school photo? My great-aunt Ivy Scott almost certainly knew your great-uncle; she was born in 1896 and lived much of her life at 410 N. 7th St in Apollo – just down the block from the Harringtons! Family lore has it that they originally lived in ‘Sugar Hollow’, a location I never could locate until quite recently. I’m not sure when they moved to the house on N. 7th; I do know she moved out and to Cleveland in the early 1980s when her diabetes precluded going down to the basement to shovel coal into the furnace anymore =:o We sort of lost track of what happened to the house after that, but it’s still standing; presumably now with more modern heat.

LikeLike

Hi Wolfkitten, I am sorry for my very very delayed reply! I somehow missed your message until now. I have no further attributions to that school photo. It had belonged to my great-grandmother, and on the back it listed only where her brother George Harrington was standing. It’s interesting to hear that your great-aunt Ivy lived at 410 N 7th Street — I agree, your great-aunt and my great-uncle must have known each other! That house at 410 N 7th was part of Simon Truby’s original land holdings, and so was much of Sugar Hollow road. If I come across any info related to Ivy Scott while researching the Truby land records, I will let you know. Thanks for writing, and again, sorry for my delay!

LikeLike